You have, no doubt, heard of the Rhodes Scholars.

That august group counts among its alumni Bill Clinton and Kris

Kristofferson. Less well known but perhaps more prestigious, however,

are the Oates Scholars: an elite corps of renunciants who spend years

cloistered away in abandoned luncheonettes poring over the Hall and

Oates canon in an attempt to decipher the esoteric messages embedded

therein.

It should come as no surprise that the members of Koot Hoomi are former Oates Scholars. We can tell you exactly who produced War Babies and why Daryl Hall’s Sacred Songs was initially withheld from the public. We may not be able to explain the theory of relativity, but dagnabbit, we do know the year “She’s Gone” charted.

In recent years, we have been visited by tribes of earnest young seekers drawn to the Hoomi’s Lair as if by the North Star. They come from all the established civilizations of the Nine Planets*, yet despite their cultural differences, they all arrive armed with the exact same question.

“Esteemed Members of Koot Hoomi,” they say, “We wish to commit to the Way of Oates, but we do not know where to begin. The back catalog is simply too extensive. Please point us to the most sacred platters.”

As a service to them, and to you—and, quite frankly, since we’re tired of answering the door and speaking to homeless crackpots from Neptune—we have taken it upon ourselves to compile a list of our ten favorite Hall and Oates albums. Your Way may be different from our Way, but the melodies etched into the grooves of these phonorecords have, for us, unlocked the harmonic codes of the universe.

#10: Marigold Sky. Those familiar with the canonical works of Hall and Oates may be scratching their heads at this one. After all, the general academic consensus is that the Golden Age of H&O concluded with Big Bam Boom in 1984. We’re not necessarily disputing that, but we also know that greatness doesn’t just get turned off like a spigot. There have been sporadic flashes in the ensuing years and this is one of them. If any other artist were to include tracks such as “Romeo is Bleeding,” “Throw the Roses Away,” and “Marigold Sky” on the same album, it would be declared their masterpiece. For Hall and Oates it’s just a good album.

#9: Big Bam Boom. 1984 found Daryl and John sitting astride the world like colossi. Surely they were tempted to simply sign, seal, and deliver a rehash of their formula to the teeming masses. Instead, they served up a pop album nearly bursting with melodic innovation. From the swaggering power chords of “Out of Touch” to the dizzying calypso rhythms of “Method of Modern Love” to the dissonance of “Some Things are Better Left Unsaid,” Big Bam Boom is both radio-friendly and creative. Even the weaker tracks, such as “Possession Obsession,” are better than you remember.

#8: Daryl Hall: Sacred Songs: Okay, this is one of the apocrypha, and is therefore not a required text for Oates Scholars. Nevertheless, it’s awfully hard to go wrong with a collaboration between Daryl Hall: the king of blue-eyed Philly soul, and Robert Fripp: the high priest of progressive rock. This is an alchemical stew of doo-wop, psychedelia, ambient soundscapes, and angular hard rock. “Without Tears” is a beautiful homage to Aleister Crowley. Seriously.

#7: Rock and Soul Part I. If you need a quick shot to get you through the day, this is the one. This compilation includes “Kiss on My List,” “Private Eyes,” “Say It Isn’t So,” “Rich Girl,” “Maneater,” and on and on. The sheer weight of all these hooks is staggering.

#6: H2O. Oates Scholars are already well aware that beneath the glossy sheen, this is dark, dark, dark. Have you ever sat down and really listened to the lyrics of “Maneater”? How about “Open All Night” and “Crime Pays”? Or the Mike Oldfield cover “Family Man”? Even “One on One” is a song of emotional isolation. He’s tired of playing on the team, folks. And on “Italian Girls,” John Oates asks the very same question that has perplexed archeologists, sociologists, genealogists, cosmologists, and cosmotologists for centuries: “Where are the Italian girls?”

#5: Whole Oats. We see the through-line from “Waterwheel” to the vocal stylings of Thom Yorke. Maybe Thom doesn’t, but that’s not our problem. This folk-rock-soul hodgepodge also contains the wonderful “I’m Sorry,” “Goodnight and Goodmorning” and “Lilly.” Harmonies come tumbling out of every rickety closet door you open. Plus, it took serious balls to put the magnificently loopy “Georgie” (which features the line “The girl caught her locket / on an underwater branch / and the next thing she knew / she had died”) as track #3.

It should come as no surprise that the members of Koot Hoomi are former Oates Scholars. We can tell you exactly who produced War Babies and why Daryl Hall’s Sacred Songs was initially withheld from the public. We may not be able to explain the theory of relativity, but dagnabbit, we do know the year “She’s Gone” charted.

In recent years, we have been visited by tribes of earnest young seekers drawn to the Hoomi’s Lair as if by the North Star. They come from all the established civilizations of the Nine Planets*, yet despite their cultural differences, they all arrive armed with the exact same question.

Oates Scholar puzzles over the original manuscript of "I'm Just a Kid, Don't Make Me Feel Like a Man."

“Esteemed Members of Koot Hoomi,” they say, “We wish to commit to the Way of Oates, but we do not know where to begin. The back catalog is simply too extensive. Please point us to the most sacred platters.”

As a service to them, and to you—and, quite frankly, since we’re tired of answering the door and speaking to homeless crackpots from Neptune—we have taken it upon ourselves to compile a list of our ten favorite Hall and Oates albums. Your Way may be different from our Way, but the melodies etched into the grooves of these phonorecords have, for us, unlocked the harmonic codes of the universe.

#10: Marigold Sky. Those familiar with the canonical works of Hall and Oates may be scratching their heads at this one. After all, the general academic consensus is that the Golden Age of H&O concluded with Big Bam Boom in 1984. We’re not necessarily disputing that, but we also know that greatness doesn’t just get turned off like a spigot. There have been sporadic flashes in the ensuing years and this is one of them. If any other artist were to include tracks such as “Romeo is Bleeding,” “Throw the Roses Away,” and “Marigold Sky” on the same album, it would be declared their masterpiece. For Hall and Oates it’s just a good album.

#9: Big Bam Boom. 1984 found Daryl and John sitting astride the world like colossi. Surely they were tempted to simply sign, seal, and deliver a rehash of their formula to the teeming masses. Instead, they served up a pop album nearly bursting with melodic innovation. From the swaggering power chords of “Out of Touch” to the dizzying calypso rhythms of “Method of Modern Love” to the dissonance of “Some Things are Better Left Unsaid,” Big Bam Boom is both radio-friendly and creative. Even the weaker tracks, such as “Possession Obsession,” are better than you remember.

#8: Daryl Hall: Sacred Songs: Okay, this is one of the apocrypha, and is therefore not a required text for Oates Scholars. Nevertheless, it’s awfully hard to go wrong with a collaboration between Daryl Hall: the king of blue-eyed Philly soul, and Robert Fripp: the high priest of progressive rock. This is an alchemical stew of doo-wop, psychedelia, ambient soundscapes, and angular hard rock. “Without Tears” is a beautiful homage to Aleister Crowley. Seriously.

#7: Rock and Soul Part I. If you need a quick shot to get you through the day, this is the one. This compilation includes “Kiss on My List,” “Private Eyes,” “Say It Isn’t So,” “Rich Girl,” “Maneater,” and on and on. The sheer weight of all these hooks is staggering.

#6: H2O. Oates Scholars are already well aware that beneath the glossy sheen, this is dark, dark, dark. Have you ever sat down and really listened to the lyrics of “Maneater”? How about “Open All Night” and “Crime Pays”? Or the Mike Oldfield cover “Family Man”? Even “One on One” is a song of emotional isolation. He’s tired of playing on the team, folks. And on “Italian Girls,” John Oates asks the very same question that has perplexed archeologists, sociologists, genealogists, cosmologists, and cosmotologists for centuries: “Where are the Italian girls?”

#5: Whole Oats. We see the through-line from “Waterwheel” to the vocal stylings of Thom Yorke. Maybe Thom doesn’t, but that’s not our problem. This folk-rock-soul hodgepodge also contains the wonderful “I’m Sorry,” “Goodnight and Goodmorning” and “Lilly.” Harmonies come tumbling out of every rickety closet door you open. Plus, it took serious balls to put the magnificently loopy “Georgie” (which features the line “The girl caught her locket / on an underwater branch / and the next thing she knew / she had died”) as track #3.

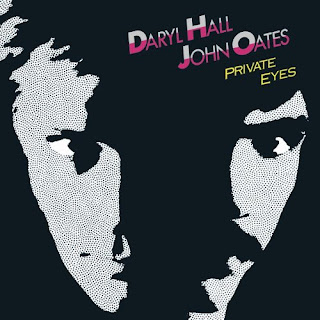

#4: Private Eyes.

Punchy, catchy, and just plain marvelous from start to finish.

Highlights: “Unguarded Minute,” “Your Imagination,” “Head above Water,”

“Did It in a Minute,”

“I Can’t Go for That,” “Mano a Mano,” and, of course, the title track. The songs you don’t recognize are every bit as good as the ones you do.

#3: Abandoned Luncheonette. Earthy. Sophisticated. Self-assured. Oates firing on all cylinders and more than holding his own against the heaven-scraping ululations of the tall blonde mangod who shares his destiny. This is the work of a duo. It would never be quite this democratic again, but that’s okay. We have this sonic artifact imbued with celestial fire.

#2: Hall and Oates: The Early Years. Not an official album per se, just a collection of mostly acoustic guitar-and-piano demos. But it was this compilation that set Koot Hoomi on the path to the Dark Side. We fell in love with the unadorned beauty of those two voices—Daryl’s angelic tenor and John’s elemental baritone—blending over softly tickled ivories and gently strummed steel strings. “Back in Love” calls out to us across the decades, laying its beating heart on the table here, now, today. The Early Years were good years. For all of us.

#1: Beauty on a Back Street. The true Dark Side of Hall and Oates. Folks, this one thrums with so much unholy occult energy that Daryl and John themselves disowned it. No matter. If you happen to find it in a bargain vinyl bin somewhere, I can guarantee it’ll be the best $1.99 you’ll ever spend. Where else can you find a pitch-perfect Led Zeppelin pastiche (“Winged Bull”), a pair of voice-lacerating screamers (“You Must Be Good for Something” and “Bad Habits and Infections”), two of the finest top-ten hits that never were (“Why Do Lovers Break Each-other’s Heart” and “Bigger than Both of Us”) and Oates blowing his soft breeze over the tumbleweeds of our souls via “The Girl who Used to Be”? Beauty on a Back Street did not need the Koot Hoomi treatment; it’s already well and truly in the twilight zone. And that’s a good thing.

There you have it. Ten platters of excellence. Ten bells in the fog. Ten cries of lamentation. Ten mortal blows to musical snobbery. Ten gifts to give your sweetheart in exchange for eternal love.

You’re welcome.

*Koot Hoomi does not recognize the recent downgrading of Pluto

“I Can’t Go for That,” “Mano a Mano,” and, of course, the title track. The songs you don’t recognize are every bit as good as the ones you do.

#3: Abandoned Luncheonette. Earthy. Sophisticated. Self-assured. Oates firing on all cylinders and more than holding his own against the heaven-scraping ululations of the tall blonde mangod who shares his destiny. This is the work of a duo. It would never be quite this democratic again, but that’s okay. We have this sonic artifact imbued with celestial fire.

#2: Hall and Oates: The Early Years. Not an official album per se, just a collection of mostly acoustic guitar-and-piano demos. But it was this compilation that set Koot Hoomi on the path to the Dark Side. We fell in love with the unadorned beauty of those two voices—Daryl’s angelic tenor and John’s elemental baritone—blending over softly tickled ivories and gently strummed steel strings. “Back in Love” calls out to us across the decades, laying its beating heart on the table here, now, today. The Early Years were good years. For all of us.

#1: Beauty on a Back Street. The true Dark Side of Hall and Oates. Folks, this one thrums with so much unholy occult energy that Daryl and John themselves disowned it. No matter. If you happen to find it in a bargain vinyl bin somewhere, I can guarantee it’ll be the best $1.99 you’ll ever spend. Where else can you find a pitch-perfect Led Zeppelin pastiche (“Winged Bull”), a pair of voice-lacerating screamers (“You Must Be Good for Something” and “Bad Habits and Infections”), two of the finest top-ten hits that never were (“Why Do Lovers Break Each-other’s Heart” and “Bigger than Both of Us”) and Oates blowing his soft breeze over the tumbleweeds of our souls via “The Girl who Used to Be”? Beauty on a Back Street did not need the Koot Hoomi treatment; it’s already well and truly in the twilight zone. And that’s a good thing.

There you have it. Ten platters of excellence. Ten bells in the fog. Ten cries of lamentation. Ten mortal blows to musical snobbery. Ten gifts to give your sweetheart in exchange for eternal love.

You’re welcome.

*Koot Hoomi does not recognize the recent downgrading of Pluto